What actually happened at Stonewall?

The riots that began on this day 55 years ago have been subject to continual revisionism. Let’s return to the facts.

If you visit Greenwich Village in New York, the sense of nonconformism seems built into the very topography. Whereas the streets of Manhattan are largely a perpendicular affair, those of the Village vary in width and intersect in unpredictable ways. In his definitive study, Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution (2004), David Carter explains that this was due to local residents’ opposition to the New York grid plan of 1817. It is as though the seeds of resistance had been sown in the neighbourhood long before the riots at the Stonewall Inn.

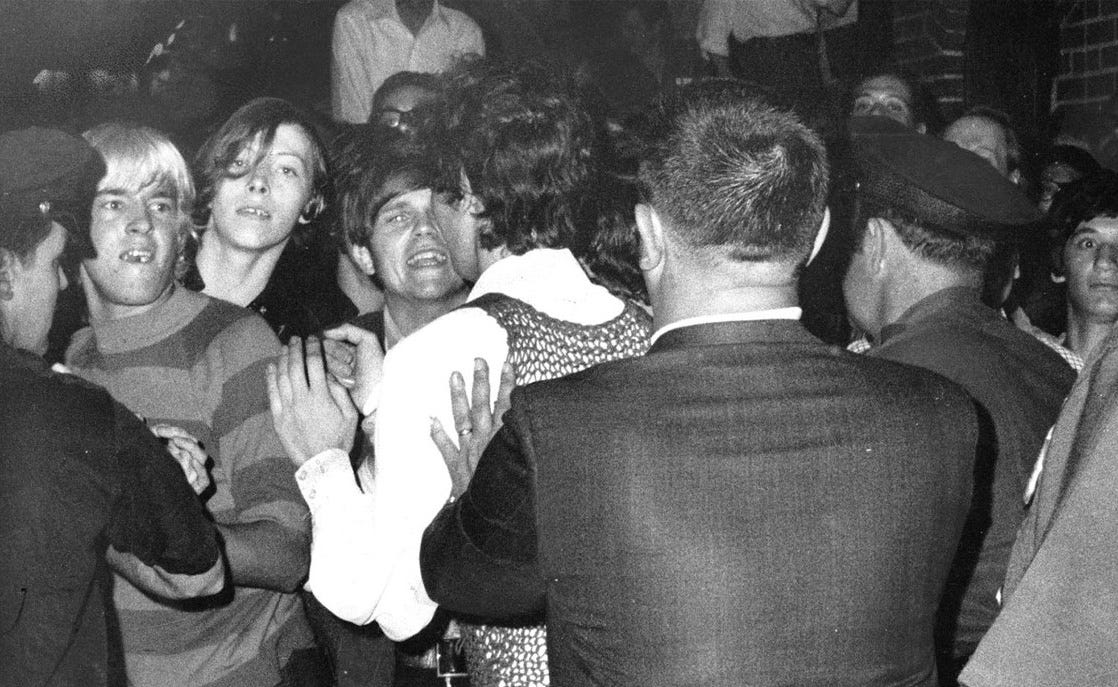

The protests that erupted at that small gay bar in the early hours of 28 June 1969 represent a turning point in the history of civil rights. While the riots themselves may not have directly resulted in societal change, the activism that they inspired in the subsequent years made a lasting difference. Yet what happened on those nights has been widely misrepresented and subjected to crude historical revisionism, from assertions that the uprising was a reaction to the death of Judy Garland, to claims that it was led by trans people of colour. For those who have seen the photographs of young gay men leading the charge, this will seem confusing. So let’s return to the facts.

At the time of the riots, animosity towards gay people was the norm. Traditionalists opposed homosexuality for the same reason they always have, seeing it as against the natural law. Progressives saw it as a mental illness, which meant they generally treated those afflicted with pity rather than scorn. Gay sex was illegal in all states except Illinois. These circumstances meant that young gay people often found themselves homeless having been disowned by their families. Many of those who fought at the riots had gravitated to the Village in the hope of finding others like themselves.

The history of the Stonewall Inn dates back to 1930, when two former stables at 51 and 53 Christopher Street became the premises for a new tearoom called “Bonnie’s Stone Wall”. It is likely that the proprietor – we assume it was a woman called Bonnie – had taken the name from Mary Casal’s gay memoir The Stone Wall which had been published that year. Carter believes that in doing so Bonnie was sending “a coded message to lesbians that they would be welcomed there”.

Over the decades the name evolved: it became “Bonnie’s Stonewall Inn” in the 1940s, then the “Stonewall Inn Restaurant” in the 1960s, and only after a fire did it rise from the ashes in 1967 as the gay bar known as the “Stonewall Inn”. By this point it was owned by the mafia. Under the watchful eye of “Fat Tony”, the bar operated in the guise of a private club to evade the city’s liquor license laws. There was no running water, so the bartenders would rinse glasses from the sinks filled in advance of each night’s shift, a practice which on one occasion resulted in an outbreak of hepatitis. Ultimately, it was the mafia’s monopoly on the city’s gay bars, and the police who saw them as easy targets, that stirred the frustrations that would eventually explode on that blisteringly hot summer night in June 1969.