You CAN shout “fire” in a crowded theatre

Tim Walz repeated the pro-censorship cliché during last night’s vice-presidential debate. It’s about time it was put to rest.

There are few people who are courageous enough to openly admit that they oppose freedom of speech, and so we would be forgiven for thinking that the authoritarian mindset is rare. In truth, those who believe that censorship can be justified typically resort to a set of hackneyed and specious arguments. It doesn’t seem to matter how often these misconceptions are conclusively rebutted, they continue to be trotted out with depressing regularity.

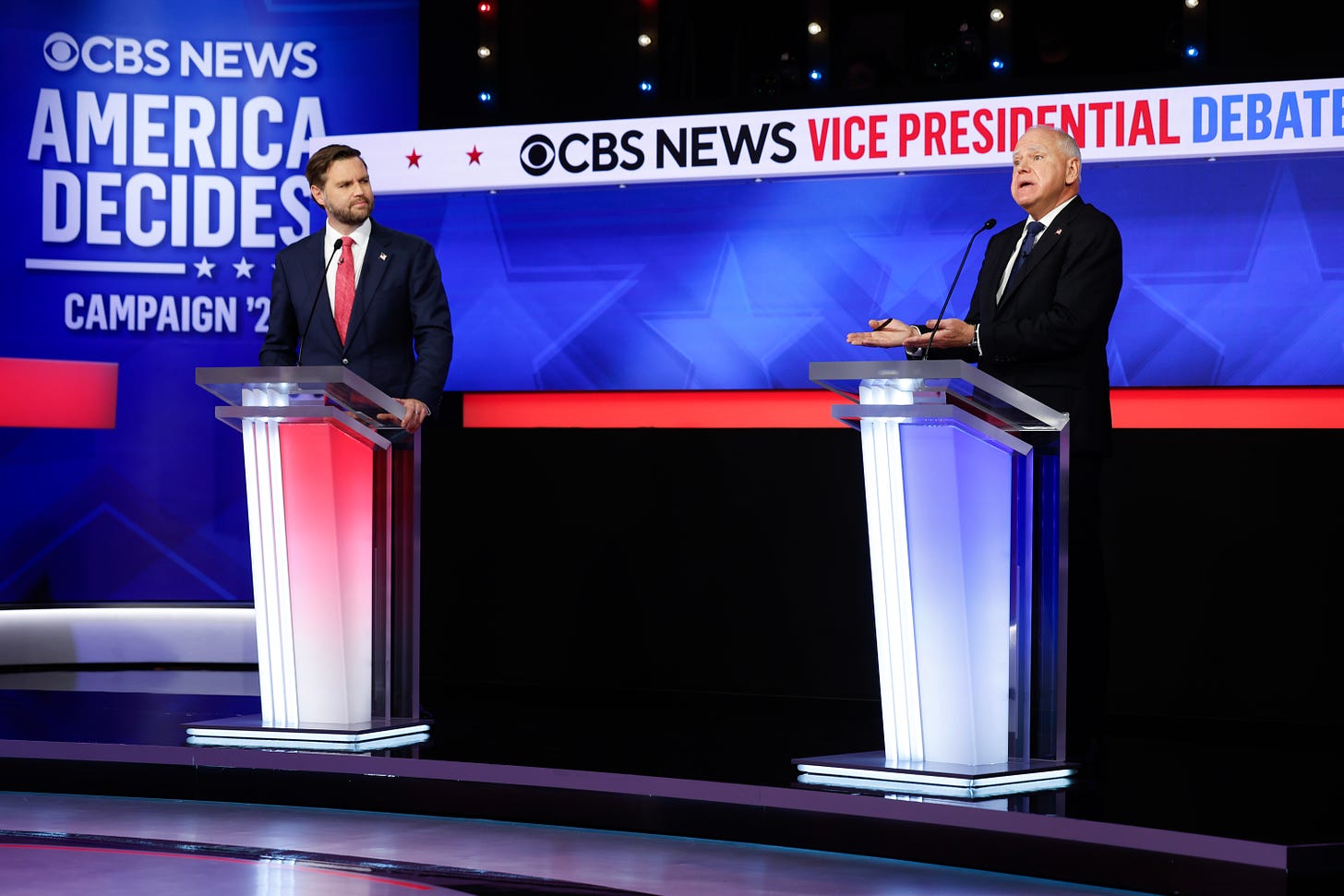

Take yesterday’s Vice Presidential debate between JD Vance and Tim Walz, in which one of these very misconceptions was parroted once again. This is how it happened:

JD Vance: You guys attack us for not believing in democracy. The most sacred right under the United States democracy is the First Amendment. You yourself have said there’s no First Amendment right to misinformation. Kamala Harris wants to…

Tim Walz: Or threatening, or hate speech…

JD Vance: …use the power of government and big tech to silence people from speaking their minds. That is a threat to democracy that will long outlive this present political moment. I would like Democrats and Republicans to both reject censorship. Let’s persuade one another. Let’s argue about ideas, and then let’s come together afterwards.

Tim Walz: You can’t yell fire in a crowded theatre. That’s the test. That’s the Supreme Court test.

The cliché that “you can’t shout ‘fire’ in a crowded theatre” originates in the 1917 United States Supreme Court ruling against Charles Schenck, a socialist who had issued a broadside calling for young men to refuse military conscription and was convicted under the Espionage Act. These were the circumstances under which Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote the statement: “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting ‘Fire!’ in a theatre and causing a panic.” Note that the word “falsely” is invariably dropped when quoted by advocates for censorship.

Leaving that telling little edit aside, it should be remembered that this was never a legally binding statement. Walz maintains that this is “the Supreme Court test”, but Holmes merely used the analogy to justify upholding Schenck’s prosecution. In fact, the decision of the court in Schenck v. United States was overruled in 1969.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Andrew Doyle to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.